Contemporary Repertoire in Orchestral Programming - Year 3, Part 2

After a busy October of performances, I am finally back writing! Starting with the slightly overdue second part of the year 3 Orchestral Programming Report. While part one provided analytics of the quantity of contemporary repertoire being performed by the six orchestras profiled, this post will examine what kinds of symphonic contemporary repertoire is being programmed, with a look at the number of premieres, commissions, and contemporary stylistic preferences of each orchestra.

PREMIERES

There are four main types of premieres - International, National, Coastal, and Orchestral. Coastal and Orchestral Premieres are unique to the United States. Coastal premieres are distinctly American for geographic reasons. ‘Orchestral Premieres’ are not advertised in Northern Europe the way they are in the United States. It could be because there are many more orchestras per capita or it is possible that Northern European orchestras are adding works to their repertory so frequently that they do not consider saying that a given work is being performed for the first time. But when it comes to analyzing contemporary music orchestral practices, studying the amount of premieres given in a season is one way to interpret whether orchestras view contemporary programming as giving ‘first performances’ (introducing new repertoire) or giving repeat performances in order to add works to the ‘classical canon’, establishing audiences familiarity with new composers. For all orchestras, it was a combination of the two, for no orchestra performed only premieres this season. There are, however, indications of preferences from orchestra to orchestra.

On average, about a third of the contemporary works performed by each of the Northern European orchestras this season was an ‘International’ or ‘National Premiere’. As you can see from the chart at left, the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic performed the fewest premieres, of 19 contemporary works last season and only 1 (5%) was a premiere. By contrast, half the contemporary works performed this season by the Danish Radio were premieres.

In the US, the average was slightly higher, at 37%. However, when one included ‘Coastal’ and ‘Orchestral Premieres’, the average number of premieres increased to 55%! As the chart at right shows, American orchestras emphasized introducing new works more than their European counterparts this season.

The chart at right shows changes in percentage of premieres (as a percentage of total contemporary works performed) from last season (2018-2019) to this season (2019-2020). Almost every Northern European Orchestra excerpt the RSPO and FRSO increased the number of ‘International’ and ‘National Premieres’. In the US, only the Philadelphia Orchestra significantly increased its number of premieres this season, while the Cleveland Orchestra decreased theirs. But considering the other types of premieres (coastal, orchestral) given by American orchestras, there remains a higher focus in the US on performing premieres, or at least advertising premieres. Separate study would be required to ascertain whether premieres are predominantly a PR tool used to “sell” contemporary music to audiences or a reflection of a cultural practice which views contemporary repertoire performance as only playing ‘what is new’. Like we saw in Part 1 of the report, however, the Danish Radio contemporary programming practice continues to have more in common with the American orchestras.

COMMISSIONS

A commission is when an orchestra pays a composer to write a piece for the orchestra. It could be a concerto for a particular solo player, or a piece for the entire orchestra. As mentioned, some American orchestras have a ‘composer-in-residence’, from whom the orchestra might commission a particular number of works during that composer’s tenure in the position. The orchestra most often performs the commission as a ‘World Premiere’ [or ‘International Premiere’], or it might perform the ‘National Premiere’ if the work is co-commission by multiple orchestras. One might assume, then, that the premiere statistics from above would be the same as the commission figures, but that is not always the case. While all ‘World Premieres' are usually commissions (unless the commissioning body is not the orchestra itself, but an affiliated association), not all ‘National Premieres’ are commissions.

The first two columns in the table at left compare the percentages of premieres (of total number of contemporary works performed) and commissions this season. As you can see, for almost all of the American orchestras, all ‘International’ and ‘National’ Premieres were commissions. (‘Coastal’ and ‘Orchestral Premieres’ were not commissions). The commission work Limina by Helen Grime was premiered at Tanglewood in the summer, which is why the performance this season was not considered a ‘World Premiere’ by the BSO.

Alternatively, in Northern Europe, in all cases except the RSPO and OPO, commissions only accounted for some of the ‘International’ and ‘National Premieres’. In the Danish Radio, for instance, half of the contemporary works they played this year were premieres, but only two of those five works were commissioned. Northern European orchestras commission around the same amount as American orchestras, but those commissions do not constitute all the premieres, as they do in the United States.

The last column in the chart above shows what percentage of the commissions were by composers from the orchestra’s home country. I was curious to see if orchestras were focused more on commissioning works by their national composers, or a mixture of national and international composers. For the third year in a row, 100% of all commissions by the Finnish Radio Symphony have been from Finnish composers and 100% of commissions from the Danish Radio have been from Danish composers. The Swedish Radio, which as a “radio orchestra” would also be expected to commission predominantly Swedish music, commissioned 75% Swedish composers in 2017-2018, 100% Swedish composers in 2018-2019, and 50% from Swedish composers this season (two out of four commissioned works). The RSPO commissions only a few pieces every year, and usually they are all or mostly from Swedish composers. HKO commissioned no works in the 2017-2018 season, one work last year by a non-Finn (2018-2019 season), but five works this season, four of which were by Finnish composers. Finally, the OPO, which commissioned works by only Norwegian composers 2017-2019, selected Norwegian composers for two-thirds of this seasons’ commissions.

By contrast, only the Philadelphia Orchestra has clearly shown preference towards commissioning American composers. In the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 season, 100% of commissions by the Philadelphia Orchestra were from American composers and this season, they commissioned the most Americans by percentage (four out of five commissions). The New York Philharmonic selected American composers for 80% of commissions last season (2018-2019), but there were no American commissions in the 2017-2018 season and around half of commissions this season were American. The BSO commissioned more American composers this season than in the previous two seasons, similar to the LA Phil, who had 60% of commissions coming from American composers in 2017-2018, 45% from American composers last season, and 50% from American composers this season. The Chicago Symphony, in addition to playing more contemporary repertoire this season, also commissioned American composers for three out of four ‘World Premieres’. The Cleveland Orchestra continues to favor foreign composers; they commissioned one work this season from Austrian composer Bernd Richard Deutsch. Last season they commissioned one work, from Cleveland Orchestra Associate Principal Oboist Jeffrey Rathbun (US), but in the 2017-2018 season they commissioned two works by Italian and Austrian composers.

Some general conclusions can be drawn from the figures on ‘Premieres’ and commissions. First, American orchestras have a greater tendency to advertise, and draw focus, on introducing new contemporary works to the repertory. There is less interest in repeat performances. Even when a contemporary work is programmed that has received many performances globally, American orchestras are eager to point out that it has never been played by this orchestra, or on this coast. Despite playing at least twice as many concerts per season as the Northern European orchestras (and that is not even including summer series concerts - most of these American orchestras work through the summer as well), the focus playing contemporary repertoire is on what is “new”. Northern European orchestras are less prone to highlighting commissioning and premieres in their advertisements, brochures and websites. This has improved every season, I remember it being quite difficult in the first year of this study to identify commissions or premieres on through the online concert calendars of many of the Northern European orchestras. My research and experiences of orchestral contemporary music programming in Finland, Sweden and Denmark indicate to me that Northern European orchestras and audiences are more accustomed to consistent and regular contemporary programming. Radio orchestras take the bulk of responsibility for commissioning, mostly from their own national composers, while city orchestras commission less. In the United States, the presence of an orchestra composer-in-residence does not necessarily mean that that orchestra will commission more repertoire. The orchestras of New York and Los Angeles have commissioned and premiered the most works this season, almost double that of the other four American orchestras. But despite the active commissioning, there is not a tendency to commission American composers, in general.

COMPOSERS AND STYLES

Continuing from this discussion of commissioning national composers, I would like to discuss the further the composers and styles that the orchestras studied performed this season. The challenge, of course, is presenting the data in a clear and meaningful way, as there is a lot of data! While I present data on American and Northern European composers being played, I am not suggesting that all Finnish composers, or all Swedish composers, or all Austrian composers are composing in the same style, or styles. There are, of course, styles related to national origin (American 1960s minimalism, French 1980s spectralism) and there are composers whose works are informed by a particular style or mixture of styles. The goals here are to see, first, whether, like commissions, orchestras are playing their ‘local’ composers or wanting to play what is ‘international’, second, if there are regional trends, and third, are there any composers that are being played regularly, year-to-year, globally.

I. National or International?

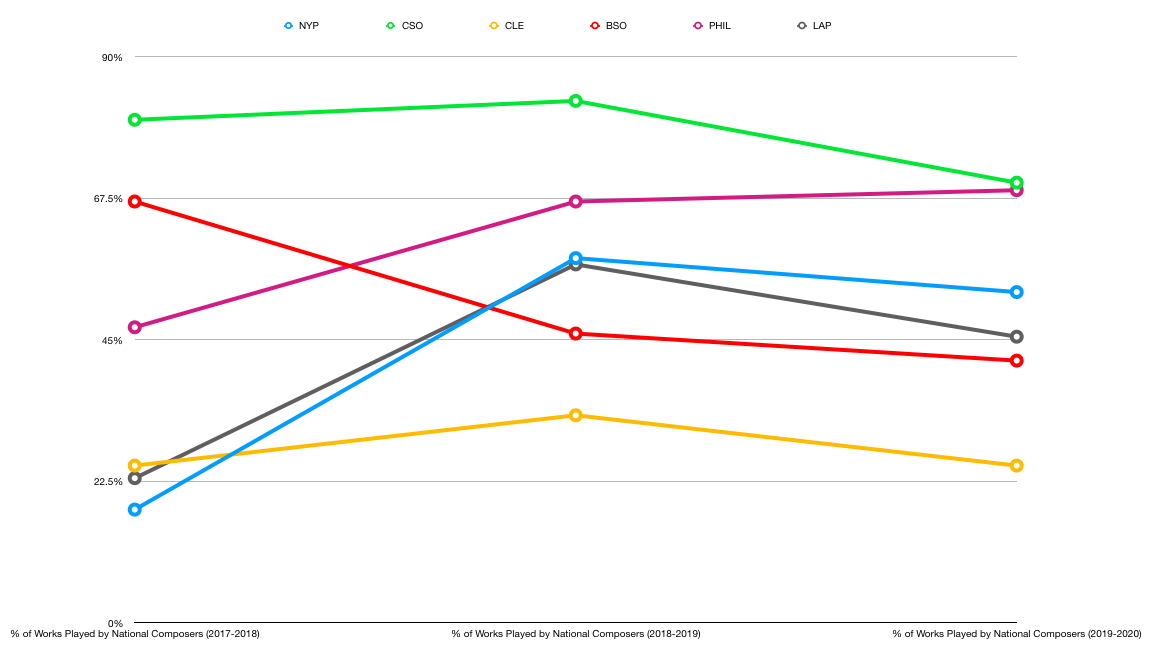

To start, here is a composite of the data from the past three seasons (2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020) showing the percentage of total contemporary works played by the ‘national composer’. For the American orchestras below, this means the percentage of American contemporary composers played. The Cleveland Orchestra has been playing the least amount contemporary American music, while the Chicago Symphony has played the most on average, with Philadelphia playing more this season than in previous seasons. The Boston Symphony has decreased the amount of contemporary American music it is playing over the last three seasons, while New York and LA have increased overall since 2017. In general, all American orchestras except Cleveland performed contemporary repertoire by American composers in at least 40% of their contemporary repertoire, with Chicago, New York and Philadelphia performing over 50% of their contemporary repertoire by American composers.

Below we have similar data presented from the Northern European orchestras. Shown are the percentage of Finnish, Swedish, Danish and Norwegian music played (depending on the respective orchestra), again as a percentage of total contemporary works played. Like in the American orchestras, there is a large range, and a lot of change over the past three seasons. What is interesting is in the 2017-2018 season, all six Northern European orchestras programmed national composers in 45-53% of total contemporary works played. From this starting point, they have diverged pretty drastically, with the Finnish and Danish Radio Orchestras increasing their playing of Finnish and Danish composers, over all, and everyone else changing quite a lot year-to-year. Where we are left, looking to next year, is that the OPO, DRSO and FRSO are playing around half or more of their repertoire by national composers, and the RSPO, SRSO and HKO playing Swedish and Finnish composers (respectively) in about a third of their contemporary repertoire.

II. Regional Trends

This section assesses any regional trends in contemporary composer performances. Are all American orchestras performing the same contemporary American composers? What is the overlap? Do the Northern European orchestras perform similar contemporary composers? Completely different?

We will look to the US first. Without generalizing too much, it can be observed that New York and LA, as the big coastal cultural capitals, do tend to perform a similar set of internationally recognized American and foreign composers, like Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Nico Muhly, John Adams (who is played most widely by all twelve orchestras, but more on that later), Esa-Pekka Salonen, Olga Neuwirth, Anna Thorvaldsdottir, Daniel Bjarnason, Matthias Pintscher, Tania Leon, Unsuk Chin, and Louis Andriessen. There are some differences, but both orchestras tend to program contemporary composers who are well-known internationally. Cleveland and Chicago, though both ‘midwestern’, have very different contemporary composer profiles. Cleveland, as discussed, programs limited contemporary American repertoire and the composers featured (Jeffrey Rathbun, John Adams, Stephen Paulus, Jennifer Higdon, John Harbison, Michael Tilson Thomas) are pretty stylistically mainstream, almost steadily ‘midtown’. The international contemporary composers performed in Cleveland are mostly German and Austrian. In Chicago, the international contemporary composers in the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 were quite well-known (Krzysztof Penderecki and Bruno Mantovani), but this season, they were mixed (Avner Dorman and Nicolas Bacri were composers unfamiliar to me, and Thomas Adès, who is very well-known). The American contemporary composers featured in Chicago over the last three season include about half ‘international’/mainstream midtowners (John Corigliano, John Adams, Jennifer Higdon, Michael Daugherty) and ‘pseudo-downtowners’ (Mason Bates and Missy Mazzoli), and a few local composers (Elizabeth Ogonek and Samuel Adams, who were composers-in-residence during the 2017-2018 season, Jim Stephenson, and Max Raimi).

Boston, New York and Philadelphia are geographically the closest but the three could not be more different in their selection of contemporary composers to program. Boston, and to some extent Philadelphia, have programmed very unique sets of contemporary American and international composers over the past three seasons. They play a couple ‘international’ names every year, but for the most part, they play composers completely different from each other, and different from the other orchestras studied. In general, the two American orchestras that have the most in common in their contemporary programming are New York and Los Angeles. Chicago and Cleveland are similar stylistically, though they lean towards national or international composers respectively, while Boston and Philadelphia have more in common with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic or Finnish Radio, featuring a unique sample of both national and international composers.

Before we look to Northern Europe, I want to briefly discuss population, because I think it is relevant to this discussion. New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago are the three most populated US cities (in that order). Philadelphia is sixth, Boston twenty-first and Cleveland is fifty-second. Stockholm, Helsinki, Copenhagen and Oslo are the capitals, and most populated cities, in their respective countries. Drawn from a quick online search, I compiled population in the table at right. I wanted to include this to get a sense of the population each orchestra is serving. With the exception of maybe Cleveland (though Ohio has a number of excellent regional orchestras), the American cities are home to more than one orchestra. I think it is fascinating that population size has little effect on programming. While New York and Los Angeles are both large, they are very different culturally and geographically. Likewise, Boston, Copenhagen and Oslo are similarly sized, but varied in their programming practices.

Looking to Northern Europe, the Finnish Radio and Helsinki Philharmonic both play a large amount of contemporary Finnish repertoire, as already discussed, but they also play very different composers. I feel this helps demonstrate the sheer amount of active professional composers in Finland, the largest per capita in the world. Not only do FRSO and HKO play different Finnish composers from each other, but they also play different composers from year to year. From 2017-2020, over the past three seasons, thirty-one different Finnish composers have been performed by the two orchestras in Helsinki. In Sweden, SRSO and RSPO have performed twenty-nine different Swedish composers over the past three seasons. Sweden, clearly, also has a huge number of composers but their population is also nearly twice that of Finland. By contrast, the only American orchestra that has come close to performing that many national composers has been Philadelphia, who have performed works by twenty-seven different American composers over the past three seasons (and they have only repeated a composer once in three seasons). Los Angeles has performed seventeen different American composers (with many reappearing season-to-season), New York sixteen, and Boston fourteen (with completely different American composers featured each season). The DRSO have performed twelve different Danish composers in the last three seasons, the OPO, ten.

Within Northern Europe, the most 'composer sharing’ happens between Sweden and Finland, with Swedish orchestras playing works by composers such as Kaija Saariaho, Magnus Lindberg, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Sauli Zinovjev, Aulis Sallinen, Einojuhani Rautavaara and Lotta Wennäkoski. Both Swedish orchestras tend to perform at least one Finnish work every season. The Finnish orchestras have played less Swedish works in the past three seasons, but works by Britta Byström and Anders Hillborg have been performed. The non-Finnish/Swedish/Danish composers performed FRSO, SRSO and DRSO each season tend to be very internationally eclectic, vary from year-to-year. While mostly European, they also include composers from Turkey, Israel, China, Japan, Argentina and the United States. The Helsinki Philharmonic is the only orchestra that publicizes a ‘theme’ for the season, and this typically shapes the programming of international contemporary composers. In 2017-2018, the non-Finnish contemporary composers were all German or Austrian, in 2018-2019 there were most American contemporary composers and this season, there has been an emphasis on Italian composition. The RSPO also programs a mix of non-Swedish contemporary composers, features many female composers, and also usually programs some Finnish and some American contemporary music every season. The OPO also features predominantly Finnish and American contemporary composers, when they are not performing Norwegian contemporary compositions.

III. Widely played composers internationally

Finally, I have looked at which Finnish and American composers are being played internationally, as Finnish and American repertoire is most closely related to my own doctoral research. American composer John Adams is the most widely played composer, internationally. Over the past three seasons, his works have been performed by all six American orchestras as well as by the FRSO, OPO and RSPO. Finnish composers Kaija Saariaho and Esa-Pekka Salonen are regularly played yearly outside of Finland. Why might that be? One factor is that John Adams and Esa-Pekka Salonen are conductors who have actively promoted both their own music, and contemporary repertoire by other generally. Composer-conductors Michael Tilson Thomas (played by the LAP in 2018-2019 and by the OPO and Philadelphia in 2017-2018) and Matthias Pintscher (performed in LA and Stockholm in the 2017-2018 season, New York, Cleveland and Copenhagen in 2018-2019, and in Helsinki this season) are also widely played, often conducting their own works. In the case of Kaija Saariaho, her international reputation is nearly unprecedented by any living composer - it was announced just this week that Kaija Saariaho has been voted the greatest living composer in the world by BBC Magazine (more here).

It goes without saying that contemporary programming has a lot to do with conductors, and, in the United States, Music Directors. When Alan Gilbert was Music Director of the New York Philharmonic from 2009-2017, he championed Scandinavian contemporary repertoire. Since his departure, the NYP has played by works by Esa-Pekka Salonen (composer-in-residence 2015-2018), but no other Scandinavian composers have been featured. As Susanna Mälkki continues conducting more and more in the United States, you see more Finnish repertoire being programmed. Likewise, co-commissions have increased over the past two seasons, prompting repeat performances and greater composer exposure. The Boston Symphony has played works by lesser-known (at least in the US) Latvian composers (their Music Director, Andris Nelsons is Latvian). It is by no means a criticism, but must be identified as an important factor in understanding what orchestras are playing. Orchestras, and their management, are more hierarchical, structurally and culturally, in the United States than in Northern Europe, especially Finland.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

With three seasons of data behind me, it seems these reports continue to get longer and more complicated. Observations of practices within a given year, which are still useful and important, are being with past seasons. I find myself trying to observe larger patterns, finding that trends are not as clear cut as I had hoped and changes between seasons can be quite dramatic.

That being said, there are a couple of general observations to be made to close this report. First, American orchestras play and advertise more premieres than the Northern European orchestras studied. Until this season, many Northern European orchestras did not even advertise clearly a “World Premiere” or a commission. And Northern European orchestras do not make any note of when the orchestra is playing a particular work for the first time. As mentioned, there are many possible explanations. But I think it does demonstrate that American orchestras consider premiering new works as important, or sometimes more important, than programming “older” contemporary repertoire. Contemporary, to many, means “what is new”, rather than understanding ‘contemporary’ as a stylistic post-modern genre of composition.

When it comes to commissioning works, the Radio orchestras of Northern Europe do the most amount of commissioning (compared to the ‘city’ orchestras), and they also overwhelmingly commission works by national composers. A variety of national composers, but national composers nevertheless. In general, all the orchestras of Northern Europe commission more national composers, on average, than the American orchestras studied. However, American orchestra have played more works by contemporary American composers than Northern European orchestras play their national composers. However, as the graphs showed, there is a lot of variety from orchestra-to-orchestra and season-to-season. This will be something to continue checking in the future.

Finally, John Adams is the most widely played American contemporary composers (over the past three seasons, amongst these orchestras) and Kaija Saariaho and Esa-Pekka Salonen are the most widely played Finnish composers. The only other widely played (in Europe and the US) European composers are Thomas Adès, Jörg Widmann, Olga Neuwirth and Matthias Pintscher. While there have been other American composers played in Europe, no composers has been played as often and as regularly (season-to-season) as John Adams. Again, this is something to continue assessing in the coming seasons.