Gestural Analysis of George Aperghis '7 Crimes de l'Amour'

Introduction

What follows is an analysis of the choreographed physical gestures in the trio 7 Crimes de L’Amour (1979) by composer George Aperghis, as they relate to musical performance. Composed for singer, clarinetist and percussionist, the work is theatrical chamber music, with each movement scored to present the players in a different ‘situations’. Each movement gives instructions on where musicians are to stand or sit, and where they are to play in relation to one another. In most movements the players remain in a single position for the duration of the movement, but in movements two, six, and seven, the players perform choreography during the movement, while playing or singing.

In the clarinet repertoire, there are works that have choreography, Stockhausen Der Kleine Harlekin being the most well-known. For me, performing this Aperghis work in November at the Kauniaisten Musiikkijuhlat was my first experience performing a work that required extensive physical choreographer, or acting, from the performer. It also requires memorization, since there is really no place to put music stands or sheet music in a performance. Aside from practical directions, the composer offers no suggestions as to interpretation or symbolism of the gestures or situations the players are in. While many performances tend to be highly sexualized, we decided in our performance to focus on the Absurdist qualities of the theatrical elements. In this paper, I analyze how the clarinetist’s physical gestures relate to the musical/playing elements in this piece.

SEQUENCE I Tous les trois comme après la fin d'un long interrogatoire, serrés côte à côte, assis face au public, le regard hagard.

In the first sequence, or movement, the musicians are instructed to sit close together, side-by-side, as if being interrogated, facing the audience, looking haggard. In our staging, the piece began with a bright spot light (Lumière violente) being turned on, directly at the players, such that we are all of a sudden exposed. The clarinetist is instructed to move the fingers over the keys of the instrument (les doigts continuent à courir sur les clés de l’instrument) for approximately 15 seconds until the singer makes a ‘lash’ (Coup de fouet). In our staging, the singer struck the stage with a horse whip, upon which we look at her, startled, and then start ‘playing’. This first physical gesture for the clarinetist, of running the keys over the clarinet, I interpreted as a nervous gesture or a tick. I interpreted hagard as more worryingly distraught; I stared nervously, shocked, at the bright light, and ran my fingers nervously over the instrument, as if it were an intuitive coping gesture to a stressful situation.

At the whip sound, we are ‘awoken’ from our individual ‘interrogations’ and engage in our own, individual choreography. For the clarinetist, the notation begins as follows:

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence I, mm. 1-5 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

The instruction is to ‘stop playing because my head is tilted back - the clarinet remains in place - and comes back as if the head was attached to a pendulum’. Then in the playing measure, the clarinetist is instructed to play pianississimo (very, very softly), sing at the same time as playing (chanter en même temps) and have breath sound with the notes ( + souffle). These three actions are a lot of instruction to do at the same time, with a small amount of source material. When I began practicing, I agonized over how to incorporate singing, and breath, and sound, and softness. However, when one considers the physical gesture with musical statement, I translated that the musical phrase could played as if the mouth is barely coming to the instrument, as if the clarinetist is trying to play, but the head is being drawn back before she can properly fix her embouchure to the horn. This is how I practiced individually, and it became a practical necessity when performing the part with the group, because the speed of the movement is such that it is a rush to coordinate the head movement and playing with the rest of the ensemble.

The influence of the physical gesture on my interpretation of the musical gesture - that the clarinetist is being pulled away from the instrument and struggles to gain hold of the mouthpiece long enough to play without a breathy, soft sound - applies to the climax of the movement. Through most of the sequence, the clarinetist only plays one measure before her head is draw back, but at two moments, she is permitted to play two measures together:

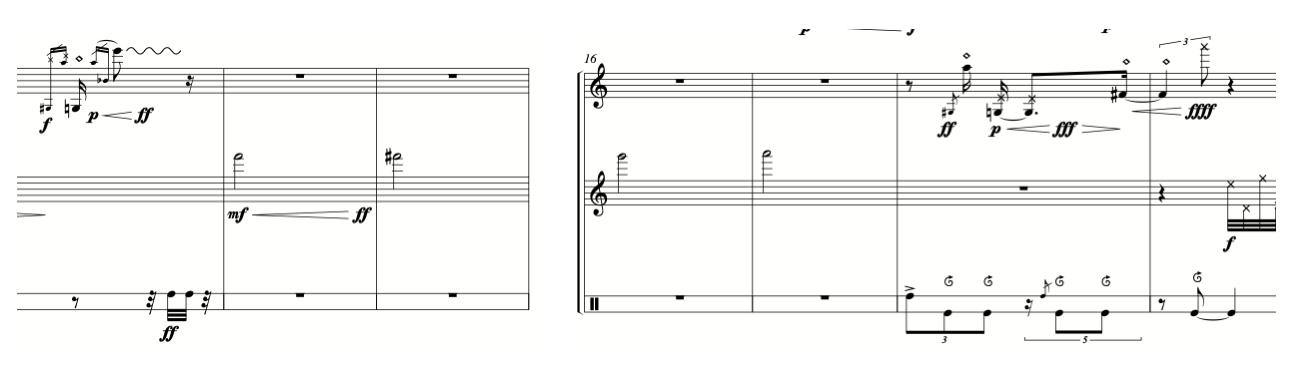

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence I, mm. 8-9 [left] and mm. 12-13 [right] (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

In the first example at left, the clarinetist is able to reach a fortississimo, only to become almost ashamed, or shocked, by herself and drop back down to a pianississimo. In the second example at right, the clarinetist crescendos quickly from ppp to ff, as if to assert herself now that she finally has time to play without her head being drawn back. After this climax, however, the clarinetist returns to 1-measure episodes, ppp until the end of the sequence.

SEQUENCE II La chanteuse à genoux tient au-dessus de sa tête le zarb. La clarinettiste joue dans le zarb, debout à droite de la chanteuse. Le percussionniste écoute, l’oreille contre le zabre et parle dans un tube de clarinette, sur l’oreille de la chanteuse.

In the second sequence, the singer is instructed to kneel while holding a zarb (Persian drum) over her head. The clarinetist stands to the right of the singer, turning to play with the bell of her instrument directed into the base of the zarb. The percussionist stands on the other side of the singer, ear pressed to the head of the drum (‘listening’), and playing/speaking into the tube of a (second) clarinet towards the ear of the singer. This is the only physical choreography for the entire sequence. As we discussed in our rehearsals, there are many possible interpretations of the physical set-up. There is a clear link between the clarinetist and percussionist, independent of the singer, with the zarb serving an a conduit. There is a chain of musical effect, whereby the clarinetist starts, the percussionist responds to the clarinet, and the singer responds to the percussionist:

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 2, mm. 1-5 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

Alternatively, one could make the argument that the clarinetist and percussionist are responding to each other simultaneously and the singer is reacting to that duet, or to the percussionist, in her own way. As our rehearsals continued, I tended to lean towards this interpretation. I tried to play to the percussionist, physically and musically, reacting at the same time to his physical and musical gestures towards me. The singer’s relationship, of having the bell of the clarinet near her ear and her reacting to that, becomes a situational side effect of the physical properties of the clarinet and the posture of the percussionist; rather than the percussionist intentionally ‘sending’ his physical and musical gesture towards her.

In all the text written for the singer, percussionist, and clarinetist through the work, there are no ‘words’, only syllables and sounds. The ‘ach’, ‘och’ and ‘ech’ in this movement are guttural, primal, sexual sounds. But they also lend themselves to the absurdity of the choreographed situation. The percussionist cannot make ‘words’ because he is ‘speaking’ into the tube of the clarinet. The singer can make words, but does not, presumably because she is imitating or reacting to the percussionist.

SEQUENCE III La chanteuse est couchée sur les genoux des deux instrumentistes. Elle tient contre sa bouche un tube de clarinette vertical. Le clarinettiste applique la clarinette sur la gorge de la chanteuse. Le percussionniste joue sur la plante des pied de la chanteuse.

The physical choreography of this sequence remains unchanged throughout. The singer lays across the knees of the seated musicians, with the tube of a clarinet coming from her mouth vertically into the air. With the singers head on the lap of the clarinetist, the clarinetist plays her clarinet into the throat of the singer. With the singers feet on the lap of the percussionist, the percussionist plays the soles of the singers feet. The composer, or editor, also provides as visual cartoon of this in the score, shown above.

As I suggest of the percussionist vocalization of the second sequence, the physical gesture of the clarinet in this sequence has a strong relationship with the vocalization. In the second measure, shown at right, the clarinetist is instructed to speak and blow/breathe into the instrument (which is in the singer’s throat). The vocalization into the throat of the singer serves to both muffle the sound and stimulate the singer. The clarinetist then, perhaps reacting to the percussionists playing of the feet, plays briefly in a quasi-normal fashion, which then does stimulate the singer to sing, as if the opening four bars are very slowly arousing the singer.

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 3, mm. 2 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

The opening six bars then repeat, beginning below in measure seven, and ending a loud climax for all three musicians.

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 3, mm. 6-15 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

The musical material in this movement is limited, but related in every way to the physical gestures. The way I musically translate my notated score, as a stimulation of the singer, is directly related the physical choreography of the movement. In the final measures, the relationship between the singer and clarinetist, and the physical gesture embodied, generates the singers chromatic ascent and my crescendo tremolo. The climax then releases the singers vocal line of nonsensical syllables, with the percussionist and clarinetist disappearing to niente.

SEQUENCE IV : la leçon de musique (the music lesson). La chanteuse est assise et mange une pomme. D’une main elle tient sure ses genoux la partition du clarinettiste qui, lui, est agenouillé devant elle. Juste derriére lui, le percussionniste assis.

A visual illustration of the movement is provided for this sequence and there is also a subtitle, ‘the music lesson’. This is the only sequence with a subtitle. The subtitle, apple and physical relationship provide the clearest narrative of the seven sequences. The clarinetist, the student, kneels before the teacher, who holds an apple and the score of the student. The percussionist is seated behind the clarinetist. In our interpretation, the percussionist serves as the accompanist for the lesson, involved musically but emotionally distanced from the relationship between the student (clarinetist) and teacher (singer).

A physical gesture begins the movement (the singer takes a bit of the apple, loudly), similar to the way the singer starts the first sequence with the loud gesture of the whip slap. However, unlike in the first sequence where each musician plays and gestures independently, in this movement, I found the clarinetist’s music a direct reaction to the physical and music gestures of the singer.

I ‘acted’ in this movement as an obedient student trying to please a demanding teacher. I begin by playing my score, a reaction to the loud bite of the apple, beginning the lesson:

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 4, mm. 1-4 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

In the second measure, the clarinetist enters. I interpreted the piano dynamic and singing sounds (in the notes with x through the stem) as having the effect of hesitation, and of stumbling. The third measure is nearly impossible to play as written, with the quick multiphonic and changing dynamics (very loud to soft to very loud). But I think that is intentional, as the student/clarinetist is trying to perform the difficult notes as accurately as possible, the result is nervous, anxious, and not ‘accurate’. The singer’s entrance in measure four, on a high E-flat, is a sudden interruption of the clarinetist, and a reprimand of sorts. The clarinetist enters again, trying to do better, only to have the teacher loudly take rapid and noisy bites of the apple, as if commentating on the student’s playing, while the student is playing (below mm. 9-11).

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 4, mm. 9-11 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

The student continues to try and do better, until the climax of this sequence, when the teacher ‘yells’ at the student. The singer suddenly enters, solo, on a high F-natural, ascending to a high G. In these measures, I cowered before the teacher, staring frightened into her eyes. I make one last attempt to get the phrase “right”, correct in mm. 18-19, ending on a ‘as high as possible’ note ffff. To me its like a written clarinet squeak, when a high note comes out accidentally.

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 4, mm. 13-19 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

But the teacher responds with the apple eating, which the obediently student tries to imitate again. The lesson ends abruptly with the singer’s aggressive solo bites of the apple, similar to the way the movement started. I am silenced by the physical gesture of her eating the apple, and remain paralyzed for the final measures.

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 4, mm. 19-23 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

SEQUENCE V Les trois acteurs < travaillent > leurs sons comme des artistes qui auraient planté leurs établis là. Ils ne se voient pas. Chacun est concentré sur son travail.

In complete contrast to the physical and sonic ‘loudness’ of the fourth sequence, this is the softest and sparsest sequence of the work. The three actors (not musicians, but actors) ‘work their sounds like artists who would have planted their workbenches there’ (I do not speak French, this is a rough translation). In other words, the actors are artists working independently in assigned places, not seeing each other, very focused on their individual work (their individual sounds). The entire movement form a type of soundscape. The three actors all sing or play (the percussionist sings into the zarb) a concert B-natural throughout the entire piece, all pianississimo. The actors never play/sing at the same time, but all overlap.

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 5, mm. 1-5 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 5, mm. 9-11 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

Above is the first five measures of the sequence. As you can see, each note has a different instruction, for the clarinet, the first measure is normal sound (without vibrato), then multiphonic, then vibrated multiphonic, then singing at the same time as playing with vibrato, then singing to crying. By virtue of the increased amount of air required to play each subsequent effect, there is a natural crescendo throughout, but I try to make this as minimal as possible. Rather than attempting to memorize each instruction, measure to measure, I viewed my part as a development of the B-natural pitch, as a painter might experiment with different shades of the same color. I also did not listen to either of the other two musicians, until the very end of the work, shown at right.

In the final measures, all ‘actors’ play/sing only with the air, then inhale suddenly to end the piece. It is notated at left (mm. 9-11). Only here, at the end, are the actors suddenly aware of one another. This is notated musically, but also physically by the inhalation gesture. We intuitively, though not written, all sat up suddenly, jerking our heads back, when we did the final inhalation at the end of the movement.

SEQUENCE VI Le percussionniste assis. Face à lui et debout, le clarinettiste et la chanteuse portent leurs clarinettes de part et d’autre de son cou, et dessinent un mouvement de va-et-vient (scie).

In this movement, the percussions remains seated, with no extra-musical choreography. The clarinetist and singer, face him on either side, and use the clarinets they are holding to make a sawing motion back and forth across his neck. There is no other instruction; it is not clear in the score whether the motion is supposed to be violent, stimulating or just visually absurd. The appearance of the clarinets moving in opposite directions on either side of the percussionist’s neck - one in front and one behind - frames his head, separating his head from his hands and the percussion instruments he is playing. Visually, this is a very geometric, mechanic visual image.

Both the singer and clarinetist speak, or sing, their parts, with no specified syllable or words. Below, the opening five measures:

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 6, mm. 1-5 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)

The arrows under the staff indicate in which direction the sawing motions should be. Of all the gestures notated in the score, coordinating the sawing motion with our individual parts, and each other, was the most challenging choreography in the entire work. The singer and I decided to make our sawing motions very deliberate and very firm, like we were dragging and pulling the clarinets through something very thick. The slow tempo notated indicated to us that the motion should be very elongated, and we stared in a very focus way at the clarinets as we made the sawing motion.

The vocalizations were independent, musically, from the sawing motion. They also were quasi-improvised, and independent from each other. The only exception was in the third measure, marked fff. There, we decided to make a very exaggerated outburst, with my shriek or scream in reaction to the percussionist, and the singer in reaction to me. Then we immediately went back to our world of softness. In musical and physical interpretation, this movement was the least obvious, in my opinion. And so our performance emphasized the ‘absurd’ and random, rather than trying to offer a theatrical interpretation.

SEQUENCE VII

The final sequence is a collage of the sixth, fourth, fifth, second and first sequences. There are no additional instructions, like in the preceding three movements. The actions are written throughout the movement. Interestingly, the third sequence is not quoted in this movement, perhaps for the reason that the choreography of the singer laying across the laps of the other two musicians could not be musically incorporated. Or, the sequence exists more independently, musically and physically, from the other sequences.

Below is the movement in its entirety, and I have marked where the ‘quotations’ from the other movements occur.

Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence 7 (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html, analysis in red added by me)

The longest recapitulation is taken from Sequence IV. This could be for musical and choreography reasons (it is a complicated movement and requires the most time to repeat), or because the movement could be considered the climax of the work (musically and proportionally). It is also interesting that Aperghis does not go in reverse order, the repeat of Sequence V comes after Sequence IV rather than before. We struggled to decide, as an ensemble, how to relate the sequences to one another. Were the seven sequences meant to be independent episodes or related events? Was there a narrative development through the sequences, or were they snapshots?

There is no correct answer, obviously. The montage of events in this seventh sequence presents both how related and unrelated the musical and physical gestures are in each sequence. Ultimately, I have come to view each sequence as narratively independent. Aperghis uses physical/theatrical gestures, syllabic pronouncements (never words), and instrumental sound effects in each movement, unifying the work as a collective whole.

Concluding Remarks

The gestural analysis of this work demonstrates the remarkable artistic connection between theater and music accomplished by Aperghis in this work. Influenced equally by both theater and music, Aperghis worked in a unique genre generating artworks reflecting an array of aesthetic influences. He also composed for a specific set of artists with whom he collaborated. The clarity of his intentions is made more apparent with repeated performances, as well as continued analysis.

![Aperghis 7 Crimes de l’Amour, Sequence I, mm. 8-9 [left] and mm. 12-13 [right] (source: http://www.aperghis.com/download-scores.html)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a902776b105987c3bab1797/1574687829323-UNHDXNLRE58XDZ9Q70NH/Aperghis+Sequence+1+Ex+2.png)