Korvat Auki: Performance-Led Research of Finnish Contemporary Music

This post will be a write up of the presentation I gave this week at the RMA (Royal Music Association) Study Day on Nordic Music at the University of York. Having never been to a UK research event, or a study day, this was a really great opportunity for me to experience this type of academic event and meet other researchers working with Nordic music. It also happened that most of the presentations centered on Finnish music, which was fun.

For this presentation, I made an attempt at concretely merging my sociocultural-anthropological observations regarding Finnish culture with my perspectives as a performer regarding Finnish contemporary music. I have written over and over how Finnish contemporary music culture, and classical music culture, feels so different from American classical and contemporary music culture, but this presentation tried to analyze Finnish contemporary music and musical practice from the historical and social perspective of societal values that were cemented in the 1970s and 1980s with the political and economic stability that developed in the Finnish nation post-World War 2.

This presentation could be the result of a current academic-existential crisis - am I an anthropologist, a performer, a historian, a music analyst (ok, probably not), or a musicologist? Or some combination? While I do not wish to simplify history to make a musical point, or simplify musical analysis to prove something anthropologically, I do believe that there’s something to be said for, dare I say, a pragmatic approach to analysis of contemporary music. With its complexity and variety, it is natural that analyses and approaches of study become more complex, but if the goal is to make connections, I think simplifying, while not ignoring the complexities, might be helpful.

So here we have my presentation, with commentary. It’s certainly a work in progress, but I am happy with the seeds planted.

Finland: Small But Mighty

Opening with a short introduction to Finnish contemporary music, explained how unique the Finnish contemporary music environment is, as a uniquely large, heterogenous, and internationally recognized body of repertoire that developed and presents very differently from other European contemporary music cultures.

Furthermore, the musical developments in the country, and the connection between music and national identity, has historical rooms dating back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Many have argued that ever since Sibelius received international recognition, Finns have strongly embedded classical music within their cultural identity, and I would argue that that connection has also been a ‘tool’ used to strengthen a sense of unity and collectivity within the small nation.

Sociocultural values and norms that I have observed keenly since moving to Finland 6 years ago have become very apparent to me in classical music culture, and particularly contemporary music culture, including a non-competitiveness that breeds a embedded sense of respect for the artistic practices of others. I identify three values- equality, individuality, experimentation - that I believe unify contemporary music practice in Finland and also can be used for musical analysis.

Performance-Led History and Performance-Led Research

In Finland, there also exists a history, again from from the 19th century, of strong links between performance and contemporary music. This connection promotes a musicological study from a performance perspective. Kimmo Korhonen wrote that contemporary music in the 1980s developed in close connection with the new generation of instrumentalists that emerged in the 1970s, which displaced the choral traditions of the earlier 20th century.

Korhonen argues, furthermore, that “the rise of new music [in the 1980s] would not have been possible without skilled performers versed in the multiple challenges presented by contemporary musical idioms” (Korhonen 1995: 68). I would offer that not only did it enable contemporary compositions to be performed at a high level, but instrumentalists involved in new music production propagated the repertoire by continuing to perform it beyond the premiere.

The connection between composers and performers exists at both the institutional and individual level. The orchestras and educational institutions established by Martin Wegelius and Robert Kajanus in 1882 established a pattern for connecting orchestral performance and music education with the current composers of the time. This precedent was continued with the founding of the Finnish Radio Orchestra in 1926-27, which from the start made commissioning a large part of its musical activities. The connections between musicians and composers were also fruitful on an individual level. For clarinet, it is hard to imagine the body of contemporary repertoire to be what it is without Kari Kriikku, who has been an inspiration to living composers and a performer of their works for nearly 50 years.

As a case study, for the presentation, I decided to use Kraft. Reflecting on my performance from 3 years ago, I feel the work exemplifies the connection between the music of the Korvat Auki founders and the Finnish sociocultural values of equality, experimentation, and individuality.

"Korvat Auki" Music Society

Founded in 1977, the Korvat Auki society marked, retrospectively, the third modernist music wave in Finland of the 20th century. Much like Sibelius’ rise represented both an important musical development but also reflected a ‘right time, right place’ moment in the geopolitical environment of the 19th century, the ‘Korvat Auki’ movement, if I can call it that, was the result of both musical and geo-political developments in Finland, particularly in the after-effects of World War 2.

In the 1970s, Finland experienced important political, economic and social changes all in a very short period of time. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, for instance, many Finns had to emigrate to Sweden to find work. But by the early 1980s, economic stabilization meant that wages and standard of living became on par with that of Sweden. Finland also established the welfare state that we know today, which included universal healthcare, monetary support for studies, free education, and unemployment benefits. I argue that the social welfare system promoted a sense of unity and equality within Finnish society, cementing values of equality, experimentation and individuality. An unprecedented economic and social stability enabled Finns to experiment in their given field with the underlying societal understanding that everyone was entitled to equal benefits, regardless of their age, gender or field of study. This experimentation, and freedom to do so, resulted likewise in an acceptance of individuality in an otherwise homogenous population.

The Korvat Auki society was founded as a reaction to a period of musical change in the 1960s and 1970s, as musicians and composers exhibited a a pseudo-conservative musical backlash to the 1950s modernist wave that took place in the country. The previous new music society, The Finnish Contemporary Music Society (Nykymusiikki-Nutiksmusik Ry), which was founded in 1949, disbanded in 1967. Music in the concert hall was also abandoned by a young culture more interested in popular music and political activism in the 1970s (Korhonen: 2003: 104) and modernism was considered by many, particular in the younger generation, to be an elitist value of the upper classes. Musically, many Finnish composers turned to free tonality in the 1960s and 70s, which “manifested as neo-classicism, neo-romanticism and minimalism” (Korhonen: 2003, 104). Korhonen continued, “the rise of free-tonality had a crucial impact on Finnish music”, which greatly affected the ‘flavor’ and heterogeneity of modernism introduced by Korvat Auki composers in the late 1970s and 1980s.

The composers of Korvat Auki, many of whom were students of important Finnish modernist Paavo Heininen, banded together in 1977 to form a new contemporary music society that promoted modernist ideals to counter the conservatism they felt pervaded classical music institutions at the time. But they also exhibited a desire to make their music ‘accessible’ to audiences through an unusually concerted effort to explain their musical processes. The Korvat Auki society presented not only concerts by European and Finnish living composers, but also held talks and bonded amongst one and another through meetings, travel and sharing of ideas. They were very closely connected personally with one another, and they shared a common attitude towards contemporary modernism, exploration and experimentation, but did not adhere to a particular style or compositional philosophy. Unlike many other new music groups, they were extremely heterogenous, which I think is the reason why they have continued to exist for as long as they have (the Korvat Auki society is still active today). The modernism perpetuated by the Korvat Auki founders “no longer involved a search for something new and unheard of: it was more of an application and deepening of things that had been discovered in the pioneering stages of modernism in the 1950s and 1960s” (Korhonen: 2003, 146).

"Korvat Auki" as Performers

The 1980s modernists continued a tradition of working closely with instrumentalists and ensembles, ensuring their music was performed often and at a high level. Further, the society founders also actively performed not only each other’s music, but also the contemporary compositions of other composers from other countries.

This active performance practice led to the creation of multiple ensembles, including Toimii, Zagros and Avanti! Chamber Orchestra. In particular the “laboratory of performers” in Toimii, which included Magnus Lindberg and Esa-Pekka Salonen, was “dedicated to experimental techniques [that] inspired developments in a number of pieces” (Howell, 233).

Case Study: Kraft

I had the opportunity to play “Kraft” in May 2016 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Sibelius Academy Symphony Orchestra. The concert was conducted by Sakari Oramo, with soloists chosen from the Sibelius Academy and composer in attendance for rehearsals and performance. It was an interesting choice of concert repertoire - Rautavaara, Prokofiev, Lindberg - to celebrate the centennial of Finland’s highest music education institution, and one that speaks to the importance of contemporary repertoire to both Finnish musical education and performance.

Regretfully, I did not know three years ago that this concert would, in many ways, be the starting point of my postgraduate music study, or else I certainly would have taken more notes! But retrospectively, I use “Kraft” as an example of how modernists of the Korvat Auki founding generation exemplified the Finnish sociocultural values of equality, experimentation and individuality in their musical compositions.

Magnus Lindberg and "Kraft"

A short background on the work itself:

“Kraft” was commissioned for the 1985 Helsinki Festival, and it was composed between 1983-1985, when Lindberg was traveling extensively in Europe and spent a lot of time in Berlin, where he was inspired by the punk rock and underground popular music scenes.

Its premiere was received with great enthusiasm, and the work has remained really popular ever since, even though it is rarely performed live. It is incredibly difficult to produce, requiring a very large orchestra with extra percussion, 5 virtuosic solo parts for clarinet, piano, cello, timpani and percussion, along with an expert sound engineer (the 6th soloist). The work requires the soloists, and members of the orchestra, to play various percussion instruments and to move throughout the hall, creating a surround sound experience for the audience.

Equality

The process of preparing and performing this work is a group effort, from the musicians to the stage workers, to the producers. Even though it is a “concerto grosso”, all five soloists have equally important parts that are reliant on one and another, as well as the orchestra. One does not feel like a typical ‘soloist’ playing this work. While the technical and physical demands (running all around the hall, for instance), make it difficult to focus on any part but your own in performance, the musical product is one where no one part is really more important than another.

Further, the orchestral parts, as well, have specialist requirements - to play in different stations of the hall and to make special effects. Never before have I witnessed such enthusiasm from the orchestra at the special parts they have to play; never was there a sense of accompaniment but collaboration.

The soloists are also not only required to play their own instrument (or instruments, for the clarinetist), but everyone is required to play percussion, as well as produce various sonic effects like crumpling paper, speaking consonant syllables, or blowing bubbles into a bucket of water into the microphone.

From the perspective of the clarinetist, the soloist A is required to play four clarinets, E-flat, B-flat, contrabass and B-flat bass. This is incredibly rare for any orchestra work, let alone a concerto. And all four clarinets are equally important within the work from a performance standpoint. Each have a technical solo, with extra techniques, and each is written for idiomatically.

Experimentation

As it relates in particular to the clarinet part and the aspects of performance, “Kraft” was a musical experiment in clarinet writing inspired in large part by the soloist, Kari Kriikku.

Kari Kriikku has been integral to the development of contemporary Finnish clarinet repertoire, working with composers from the late 1970s to present day. I admittedly (and embarrassingly) do not remember specifics of much of what Magnus said during project week (I was starstruck and shy, to be honest), but I do remember him saying that the clarinet part, in particular, owed a great deal to Kari and the fact that Kari NEVER said “no” to any of Magnus’ suggestions. This allowed Magnus, I think, to really “push the envelope” of what the clarinet could do, technically and sonically. And I’m sure the work inspired later clarinet pieces by other Finnish composers as well.

There are both physical and musical experiments that the work requires of the clarinet soloist. On the more physical side- to play contrabass clarinet, a beautiful but very challenging instrument that few clarinetists have a great deal of experience with. Not only that, but the contrabass clarinet solo, which comes about half-way through the, comes right after the clarinetist must play bamboo chimes and Chinese symbol at “Station 4”. In our performance, this meant finishing playing B-flat clarinet part in measure 88, leaving the stage and walking quickly through the hall to one of the upper balconies behind the audience, playing the percussion parts, and then traveling back to the stage to pick up a cold contrabass clarinet and play the “highest note possible” on contra fff (triple-forte dynamic) to start the solo at m. 151. And the contra solo itself, about 42 measures long spanning the whole range of the instrument with a number of extra techniques, to finish the solo by making key noises into the microphone while playing castanets with the right hand.

On the musical side, the work is an experiment in trying to produce as wide a range of diverse sounds as possible. Using various notation, the composer is striving for a wide range of sounds, at various timbres and on the different clarinets. It is something I remember working a great deal on in my lessons with Kari, and I think should I ever get the chance to work on the piece again, it is an area which one could continuously work and grow on.

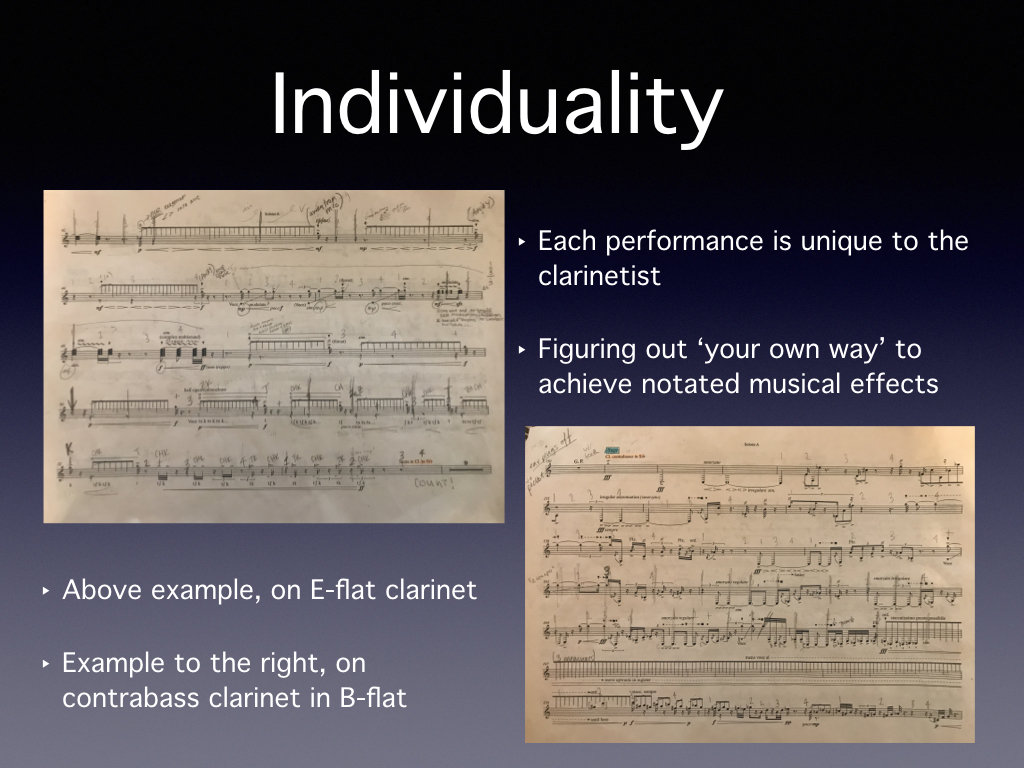

Individuality

Like all compositions, but especially with this one, there is an aspect of individuality in performing the work because no two performances will ever be alike. Every concert hall is different, so the stations around the hall called for in the score will be different, thus affecting both the visual and sonic performance. Also, the score calls for a collection scrap metal and parts to be collected from a nearby junkyard. Lindberg said the goal was for the performance to literally sound like the place it is being performed at, again, making each performance unique.

For the clarinetist, also, the score and performance practice of the work inspire each clarinetist to come up with him or her own technique for making the various extra sounds on all the clarinets. The notation is clear, but there are many different ways to accomplish what is written on the score. Prior to the performance, I had never played a work with so many extra techniques in it. In my lessons with Kari, I was hoping he would tell me specifically how a technique should be performed, but he would not, I think partly because he himself is a player constantly experimenting with new sounds and trying new things, and partly because he wanted me to find my own way.

The parts, especially the soloist parts, are open to so much interpretation that the individual player must find his or her own vision and way of producing the sounds and effects. There is no right or wrong way, as long as a wide variety of sounds is produced. For a work that has such a “cult following”, one would think it also means a strict adherence to performance practice, but individuality is really built in to the way the work is meant to be performed.

There were no pieces like this at the time, and nothing the same since has quite been composed since. “Kraft” is a work that has been inspiring, but never copied, which speaks to the aesthetics of the ‘Korvat Auki’ founders - they all respected the work of each other while staying true to their own individual aesthetics and views.