Dancing and Twirling - Doctors in Performance Conference 2018

I just returned to Finland after my first conference presentation at the Doctors in Performance Artistic Research festival/conference in Vilnius, Lithuania. I had the opportunity to hear a very inspiring key note from Professor John Rink, as well as listen to lecture recitals and paper presentations from my peers.

My own lecture recital was a case study of Dancing Solo by Libby Larsen and Twirl by Markku Klami, and the artistic approach I have taken to preparing and performing these works. I believe that I will soon have a video of my presentation, but until then, I wanted to share my slides and some written commentary from my presentation.

Why these two composers? My Doctoral Research Project is an artistic study and comparison of contemporary clarinet works by Finnish and American composers, and I chose this topic because, as an American who studied classical music about a decade in the US, but now lives and works in Finland, I have observed pretty fundamental differences in the way that contemporary music is practiced, taught, and performed in both places. There are two main goals in my research: first, to explore the artistic benefits that contemporary music affords to the ‘classically trained’ orchestral performer and second, to identify the differences in contemporary music practice in both places and why these differences exist.

So, for this case, we have two works, Dancing Solo and Twirl, both for unaccompanied clarinet. Libby Larsen, composer of Dancing Solo, was born in 1950 in Wilmington, Delaware, and Markku Klami, composer of Twirl, was born in 1979 in Turku, Finland. These are two composers who, most likely are completely unaware of each other, but actually have a lot in common.

They both studied composition at the ‘university level’ - at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki and the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. And both these schools taught the German-modernist-serialist approach to composition, an approach that both Klami and Larsen resisted, deciding to compose using a wider variety of source material.

Here we have a quote from Denise Von Glahn’s great book on Libby Larsen, Libby Larsen: Composing An American Dream. Von Glahn concludes that Larsen’s rejection of systems, like serialism, enabled her to be inspired and influenced by many more elements - music, art, nature, religion - than your typical composer.

And below, a quote from an interview I did with Markku Klami. He told me that Twirl was written in a particularly challenging moment when he was a composition student, where he thought he was ‘stuck’. And like Larsen, removing himself from a strict compositional style allowed him greater freedom of expression in his composition.

In working with Markku and reading about Larsen, I also learned that both composers have a similar to approach to time in their music, specifically to the idea of suspending and elongating time. In this quote, Libby Larsen explains her music has matured to a point to a ‘less in more’ mentality with regard to sound. In a similar way, Markku remarked in our interview that he’s been gravitating towards composing pieces where time is suspended and the music develops over longer period of time.

And Von Glahn mentions in her book a very interesting conversation she had with Libby Larsen about Larsen’s belief that “citizens of the cold”, so those who are from or live in northern climates (like Minnesota, and like Finland), have a unique and shared experience of the phenomenon known as time. “Only northerners, she claims, understand ‘the rhythm and flow of water’ in all its moods and ways, moving and motionless.” (Von Glahn, 83)

I then played the first movement of Dancing Solo, 'With Shadows', followed by the first half of Markku Klami's Twirl.

At the beginning of the lecture I identified style and time as two musical aspects I discovered these composers converge on. To analyze how these aspects manifest themselves in these two pieces, I discussed how each composer used motivic development and pulse for artistic means.

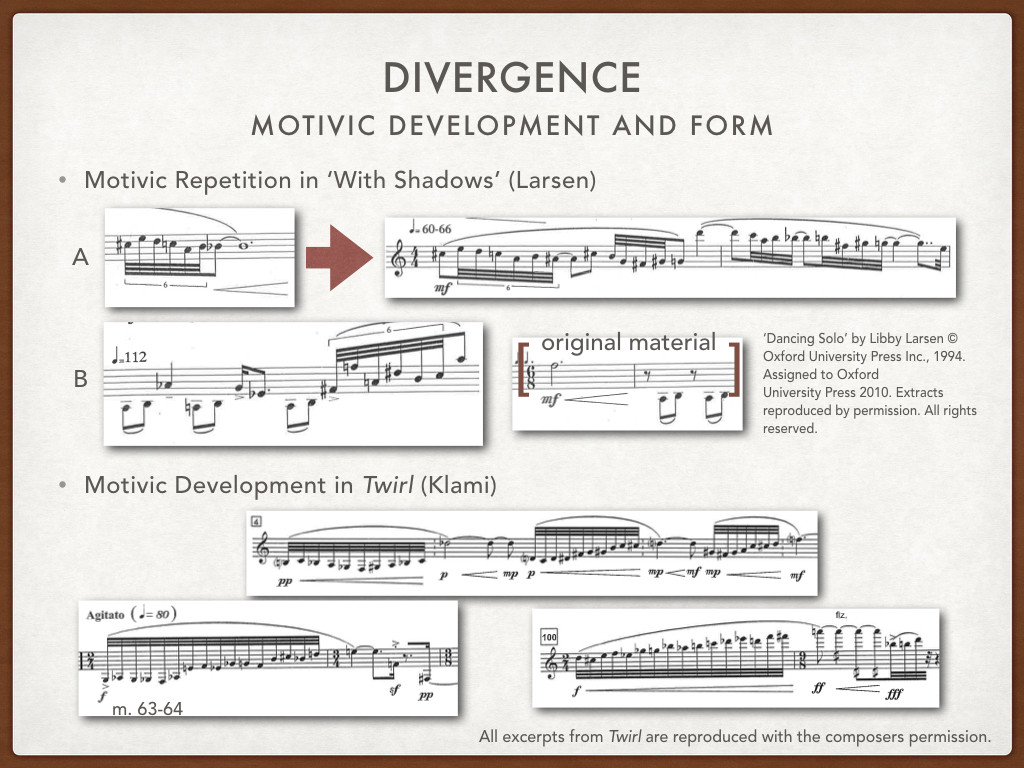

Both pieces begin with what I will refer to as a ‘figurative motive’, sextuplets, which become, in my opinion, the most important motivic source material for both entire pieces. Larsen’s sextuplet is presented three times, immediately signifying its importance to the listener. These sextuplets return identically throughout the first movement, as well as in modulated and transposed form.

Klami’s motive is slightly different; it's introduced and then developed three times in quick succession, with each iteration slightly longer and slightly louder than the previous one. And instead of holding a sustained pitch and repeating identically to draw focus to the opening statement, as Larsen does, Klami prefers to use silence, drawing the listener in closer and isolating the figuration so it is the only musical sound.

Both Larsen’s and Klami’s opening statements, contain three figurations, and both end on a long note and/or fermata, denoting a clear separation, and emphasizing importance, between these opening phrases and what follows. From here, however, the way each composer develops and uses the motive is very different.

Larsen uses repetition, and repetitions of the motives, to structure each movement of Dancing Solo. In the first movement ‘With Shadows’, the motivic sextuplet, shown here as example A, returns at the 4/4 (quarter notes equals 60-66), indicating a formal recapitulation of the opening material. The return marks a pseudo- A’, if one were to view this movements as a very loose rounded binary form. A’ begins with an exact repetition of the opening motive, reminding the listener and player instantly of the opening material, which Larsen then elaborates using the same intervallic pattern a step lower and a half step higher.

Also in the example marked ‘B’, Larsen not only transposes the motivic sextuplet, but she also recycles the 2-eighth-note pulse, shown in its original form at right.

Where Larsen uses motivic repetition, Klami uses the figuration motive more melodically as developmental source material. We already saw in the opening how quickly he began altering the opening figuration, immediately adding notes. In these short examples, one can see how the figuration motive presented at the opening gets recomposed in various forms. Despite the rapid development, what remains the same is that each figuration begins with 1/2 steps, then whole steps, and then a minor third. This intervallic relationship provides musical unity for both the clarinetist, and hopefully, the audience. Klami alters length, modulates, and recomposes these figurations, and yet somehow we can still hear them as related.

In thinking about musical time, my attention was drawn to how each composer plays with time in both works by first establishing a clear pulse, which they then can alter in different ways. In the opening, both composers begin with a ‘timeless’ space, without pulse. But Larsen establishes the pulse in the 3rd bar, shown here, at the 6/8.

Then, in the section marked push ahead, shown below, pulse gets set again, but very subtlety. The sustained dotted half notes provide rhythmic unity but also a sort of suspending of time, since the notes are held. And the pulse gets moved by the 32nd note staccati, but then de-stabilized by the accelerando.

In Twirl, Klami waits until m. 16, shown here, to set the tempo at intenso , preciso. Both the style markings, intense and precise, indicate to the performer a rhythmic stability. But Klami also changes to irregular time signatures, 7/16 and 5/8, so the pulse seems set for one measure, then changes, and then gets set again at the 3/4.

Klami sets the pulse for the first half firmly at ritmico, giocoso, m.29-33, excerpted below. This tempo remains constant from m. 29, all the way through the first half. He does, again, offset the pulse at places, in this bottom example using accents, which I’ve shown in the excerpt below using arrows, but by the end of the 2nd half, he’s returned to a very stable and firm beat.

From a performer’s perspective, I have found that recognizing the motives of each work and how each composer uses them, has been very helpful to my artistic approach. Unaccompanied works, in my opinion, are very challenging to ‘make sense of’, especially for instruments, like the clarinet, that cannot play multiple musical lines at once. In an unaccompanied work, the player has to do ‘all the musical work’ oneself, and getting a ‘big picture’ view of the work can be difficult. What helped me organize the musical structure and figure out the artistic intent of each work was to identify what I felt each composer was using to express and progress through the piece. And it happened that in both these pieces, the figurative motive was very important.

Likewise, establishing pulse in an unaccompanied piece can be challenging. Both Larsen and Klami set pulse very deliberately through short repetitive 2- or 3- note cells and through very specific tempo markings. Only once they have established tempo, can they prolong the musical phrase and elongate time.

I continued the presentation by playing the 2nd movement of Libby Larsen’s Dancing Solo, entitled “Eight to the Bar”, and the 2nd half of Markku Klami’s Twirl. I asked that the audience listen in both works for how each composer uses motivic material towards either structural or harmonic/melodic aims, and how each composer uses his and her method of motivic development to establish a distinct musical voice.

The 2nd movement of Dancing Solo, is really where I felt that Larsen established the vernacular she’s now really known for, and the one that she stays with for the remainder of the piece. Already from the beginning, shown above, she writes swing, signaling to the player a shift in style different than the first movement. Also different in this movement is the title: ‘Eight to a bar’, more of a rhythmic/quantitative title than the first movement, ‘With Shadows’.

In ‘Eight to a Bar’, Larsen again used repetition for structure and cohesion. The simple swing pattern returns throughout the work to provide unity and also establish a stylistic vernacular voice. The swing also has a much more solid inherent pulse than the material we heard in the first movement. To make even more sure that the player and audience feels the pulse, Larsen notates pulsed whole notes throughout the entire movement. I’ve excerpted one as an example here. These pulsed whole notes, in my opinion, contribute to the dialectal or idiomatic nature of this movement’s style, as well as reinforce the driving pulse by instructing the clarinetist to physically indicate pulse as part of the musical expression.

The motivic sextuplet also returns in this movement, but this time it is recomposed as a quasi-cadenza, which occurs three times in the movement, in between swing sections. Not only does the repetition contribute to the formal structure, but it also provides a contrast, stylistically and rhythmically, to the swung sections. These cadenzas serve as a suspension of time in the movement - the swing is cruising along, and then all of a sudden the tied quarter note almost feels like a fermata, pausing whatever is going on for what is about to happen. But, as you can see here, by the third ‘cadenza’, Larsen notates ‘straight’ which I took as an indication that the material is morphing more into the style the second movement, rather than the abstract presentation of the first movement. I also took it as an indication that more liberty could be taken with the first two statements.

What Larsen demonstrates in this movement, is the wide variety of musical styles that influenced her - from the expressive classical tonal to the popular and folk. And she uses the same compositional techniques - repetition of a small amount of musical materials and utilizing a rhythmic pulse.

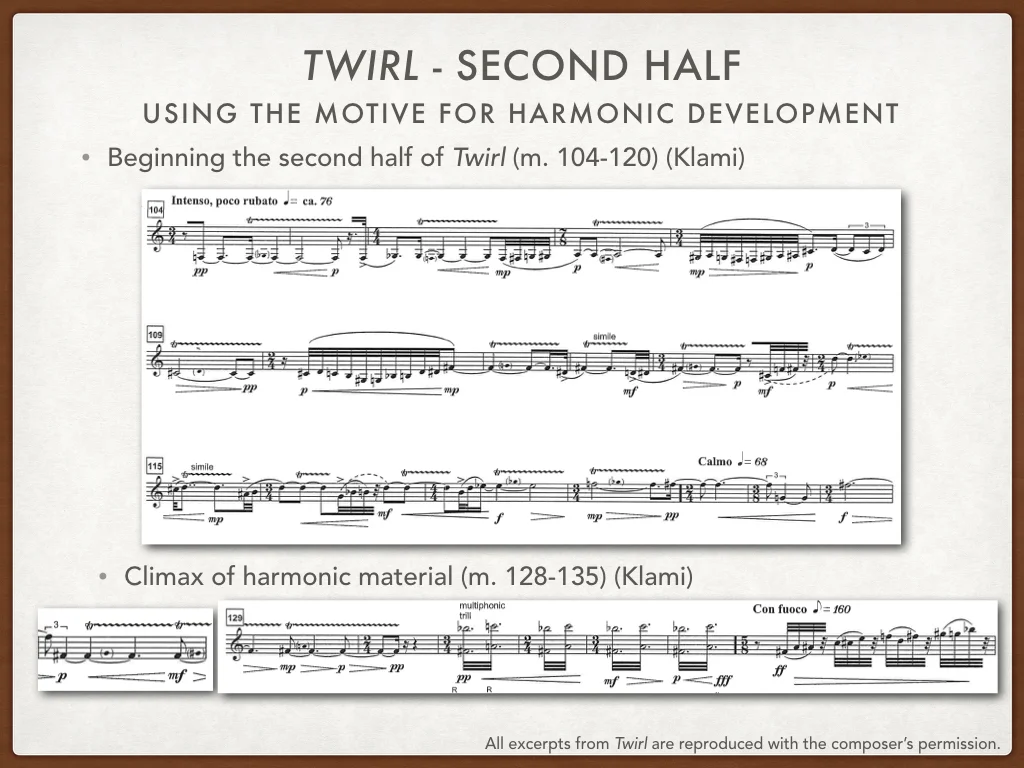

Instead of using direct and frequent repetition the source material, like Larsen, Markku Klami develops his figuration through the intervallic relationships - half step, whole step, minor third. In the second half of Twirl, especially, he intensifies the harmonic impetus of these intervals through trills and multiphonics. Klami told me that the multiphonics in this work should be considered a harmonic extension of the trills, so to me, that meant also the trills should have melodic and harmonic purpose rather than being atmospheric or ornamental.

The second half starts with a slower, intense sections, which comes right after a very dramatic build up at the end of the first half. To provide contrast in this new section, Klami composes half step trills which are intensified by small crescendi, each ascending, and connected with small figurations. The intervals of 1/2, whole and minor third define the harmonic and melodic contours, but to a different end than the rhythmic material we looked at in the first half.

This harmonic development climaxes with the multiphonic trills in m. 131-134. The harmonies intensify with the crescendi, first as a half step trill, then whole step trill, then minor third. And the multiphonic trill combines both the minor third on the both and whole step on the top. It’s as if Klami has exhausted the motivic development in this form. So what does he do? He transitions back to the rapid ascending 3-note figures from the first half, at con fuoco, leading to the last new material of the piece.

The last ‘new material’ that Klami presents in the work, might have sounded like it came out of no where - instead of slurred fast notes and soft intense trills, all of a sudden there are rapid articulated repeated notes. But I believe this section is also generated from the figuration motive, and the intervals of the motive. It first appears in measure 137 for 10 measures, and it repeats for another 10 measures leading up to the coda, but in mp. While the articulation and poco scherzando style contrast with what we heard before, the melodic contour consists of the same 1/2-step, whole-step, minor third relationships as both the figurative and harmonic material already discussed.

Klami also uses this material in the coda, winding down the piece, I’ve shown 2 examples here, before the final statement, at m. 207 con forza, of the minor third, whole step, and half step.

My musical approach to performing these works has been influenced greatly by the analysis I did into motivic development and how both Klami and Larsen approach pulse and rhythmic stability in their works. As I already said, contemporary unaccompanied works can be difficult to view holistically. I found that taking a small element like a figurative motive, or a repeated 2-3 note cell, and seeing how it develops helped me connect musical ideas that seemed unrelated when I first approached the piece.

Larsen is known for recycling a minimum number of rhythmic, harmonic and melodic motives, and understanding how she did so in Dancing Solo helped me understand how she establishes the polyglot style that she is known for.

When I first started working on Twirl, I had difficulty understanding the musical intension of the rapidly changing styles in the piece. It was only when I realized how the styles where connected that I could better understand the expressive nature of the music, and also how to pace and connect different passages together.

I finished the presentation by playing the last movement of Dancing Solo, ‘Flat Out’.

My presentation was 40 minutes long, followed by 10 minutes of discussion. In the discussion, a question was asked regarding the topic of Professor Rink's key note, the constructed/pluralistic nature of performance and what we consider 'interpretation' in a score when enacting a performance. Upon reflection, I felt that my analytical approach was not in contrary to the musical intension of either composer. I made decisions based on my analysis that I believe enabled me to perform the work in the best possible way. While my interpretation, I believe, stands in contrast to elements of Professor Caroline Hartig's great recording and past performances (to whom to the work was composed for), it does not contradict Larsen's intentions.

This conference was a tremendous learning experience, for me, and I look forward to more in the future!