Contemporary Repertoire in Orchestral Programming - Year 2 Report, Part 2

In Part Two of this report, we will focus only on the contemporary music getting played by each orchestra. Last year, in part 2 of the 2017-2018 report, I outlined a kind of ‘total contemporary music practice’ for each orchestra, based on the data gathered. While this was interesting, it makes direct comparison between orchestras, and regional comparisons difficult. I have therefore decided to simplify - I will discuss contemporary performance practice in orchestras in terms of premieres (presenting music to a public for the first time), commissions (orchestras paying for the creation of new works), the origin of the commissions (country), and which contemporary composers are getting played, and where. I have also reframed last year’s data in those terms.

PREMIERES

In many ways it is traditional to focus contemporary music performance in orchestras on premieres. The term “New Music” naturally implies music that is new, and therefore there is an attractiveness, in marketing and prestige, that comes from performing a work for the first time. But to focus only on premieres creates two problems. First, very rarely is a contemporary work ‘done justice’ in a first performance, whether that be a world premiere or even the first time a given ensemble is performing the work. Often composers, or ensembles, will make edits or corrections in later performances to improve the musical intention of a work. Performing only, or predominantly, premieres also means the audience might only get ‘one try’ to artistically absorb (or pass judgment, as the case might be) on a new composition (or composer). This leads to the second problem, which is that focusing too much on first performances, especially world premieres, does not contribute as positively towards increasing audience and musician awareness of orchestral contemporary music. Of course premiering contemporary music is better than not playing contemporary music at all, but a practice that focuses on premieres continues to treat contemporary music as only ‘what is new’. It becomes more difficult, in this way, for both audiences to ‘get used to hearing’ contemporary music, to begin to distinguish between the plethora of different styles and genres of contemporary music, and for the orchestra musicians themselves to get used to playing it.

In the 2017-2018 season, there was great tendency amongst American orchestra to focus their new music performance on premieres, with every orchestra except Philadelphia performing most contemporary works in the season as premieres. The Philadelphia Orchestra, which if you recall played the most amount of contemporary music of all the American orchestras in the 2017-2018 season, performed only two premieres in the 2017-2018 season, which is closer proportionally (around 12% of contemporary works played) to the amount of premieres made by the Northern European orchestras last season. The two exceptions last season, amongst European orchestras, were the Danish Radio Symphony, for which six out of eight contemporary works performed were premieres, and the Finnish Radio Symphony, for which 10 out of 22 works were premieres. The DRSO’s premiering practice, like their contemporary music performance practice in general, is quite similar to American orchestras. But I would argue that the FRSO, considering the sheer amount of contemporary music they play (in around 50% of all concerts, at least one contemporary work is played), it is to be expected that there exists as well a higher proportion of premieres. In general, patterns of premiere performances paralleled contemporary music performance regionally, in the 2017-2018 season. The American orchestras, minus the Philadelphia Orchestra plus the Danish Radio Symphony, played proportionally less contemporary music overall but more premieres, demonstrating a traditional approach to contemporary music where the focus is on first-time performances to attract audiences. The Northern European orchestras of Finland and Sweden performed the most contemporary music, but least premieres, proportionally. The focus is on repeated performances, which means audiences are likely more accustomed to hearing contemporary music played regularly and performers are more used to playing it.

The 2018-2019 season saw more American orchestras moving towards the European model of more contemporary music performed, but fewer premieres. The New York Philharmonic and Cleveland Orchestra both performed more contemporary music in the 2018-2019 season, but still maintained a practice of focusing mostly on premieres. The Los Angeles Philharmonic also performed a higher proportion of premieres, over 55% of all contemporary music played was a type of first performance, but they also performed contemporary music in close to 45% of their concerts. So like the FRSO in the 2017-2018, I would argue that it is natural to balance more premieres in a season where more contemporary music is getting performed. In a change, the orchestras of Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia all premiered proportionally less contemporary music in the 2018-2019 season. It will take another season to two to see if this is a permanent change, or just an anomaly. The orchestras of Northern Europe, DRSO included, likewise performed proportionally fewer premieres in the 2018-2019 season, despite significant increases in the total amount of contemporary music performed (except for the Swedish Radio, which had about a 15% drop in total amount of contemporary music performed, but about the same amount of premieres).

COMMISSIONS

Commissioning new works for orchestra from composers is important for supporting contemporary music production, and is also a larger financial investment for orchestras than simply performing new works. However, like the act of premiering, commissioning a new work and performing the world premiere offers levels of prestige for both orchestra and audience. In examining data from both the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 season, there does not appear to be any significant patterns in commissioning practices. Performing more contemporary music, in general, presents more opportunity to both premiere and commission, but it is interesting that despite some American orchestras having a particular ‘composer-in-residence’, this does not necessary account for more commissioning activity overall (or more contemporary music performance). For instance, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Philadelphia Orchestra both have ‘composers-in-residence’. Of the five contemporary works the CSO performed in the 2017-2018 season, three were commissions, compared to two of six contemporary works this season. Analysis of the CSO thus far has shown a quite high proportion of commissions, though low levels of contemporary music performance overall. In contrast, the Philadelphia Orchestra played much more contemporary music this season and last, but only commissioned one work last season and two works this season. And despite having no composer-in-residence, both the New York Philharmonic and Los Angeles Philharmonic made larger efforts to commission new works this 2018-2019 season, and commissioned the largest proportion of new music of the twelve orchestras surveyed. Of the twelve contemporary works the NYP performed in the 2018-2019 season, six were commissions, compared to only three of eleven last season. Likewise, the LAP performed eleven commissions out of twenty-three total new works, compared to five of thirteen last season.

Also interesting to look at is whether orchestras are commissioning national or international composers. There exists a strong tendency amongst Northern European orchestras to commission composers from their own country, even though they might perform a greater mixture (internationally) of contemporary music in a season. In the 2017-2018 season, over 85% of commissions by the Finnish Radio, Danish Radio, Royal Stockholm Phil, and Oslo Philharmonic were from composers from orchestra’s respective countries.* In the 2018-2019 season, the percentages were even higher, with 100% of commissions by the FRSO, SRSO, RSPO, and OPO coming from the orchestras’ respective countries. In 2018-2019, the DRSO had one Danish and one non-Danish commission and the HKO had one non-Finnish commission (their only commission that season). There is a strong sense in the Northern European Orchestras that commissioned works should be from the orchestras’ home country, perhaps a feeling that it is the orchestra’s responsibility to sponsor new works by their own composers, but perform an international mix of contemporary works.

Given the European influence on orchestra music in America, historically, it might be unsurprising that there appears to be less obligation for American orchestras to commission by works by American composers. But compared to the efforts by Northern Europe orchestras to promote works by Northern European composers, there is a weaker effort, universally, to do the same for American composers by American orchestras. In the 2017-2018 season, 100% of commissions by the Chicago Symphony, Boston Symphony and Philadelphia Orchestra were from American composers. But none of the commissions by the New York Philharmonic or Cleveland Orchestra were from American composers (and this despite the New York Philharmonic having the only American chief director, Alan Gilbert). The Los Angeles Philharmonic was somewhere in the middle, last season, with three of five commissions from American composers. The 2018-2019 season demonstrated a similar mix in the American orchestras. Only the Philadelphia Orchestra had 100% American commissions, only the Cleveland Orchestra (again) had zero. The other four orchestras fell somewhere in the middle, with an average of 46.5% of commissions by the NYP, CSO, BSO, and LAP coming from American composers. So while there is a strong effort in some American orchestras surveyed to commission American composers, but there is a less standardized practice of doing so. As I transition my research to the history of American classical music, and the history of contemporary music in the America, I think I will be able to offer some explanations, or at least why there is regionally such strong differences in commissioning practices. But for now, it remains a noticeable and interesting difference between Northern European and American orchestras and something to watch in the coming seasons.

FINNISH AND AMERICAN COMPOSERS

The final thing I would like to look at is which American and Finnish composers are being played, and where. There is a diverse group of American composers being performed in the United States, and a diverse group of Finnish composers performed in Finland and Sweden. There is, as well, a small group of Finnish composers who seem to be regularly performed in the United States, and a growing number of American composers being performed in Northern Europe.

Within Finland, both the Finnish Radio Symphony and Helsinki Philharmonic perform a diverse and large amount of Finnish contemporary each season. In the 2017-2018 season, the FRSO performed works by Olli Virtaperko, Matthew Whittall, Antti Auvinen, Lotta Wennäkoski, Magnus Lindberg, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Aulis Sallinen, Perttu Haapanen and Sebastian Fagerlund and the HKO performed works by Olli Mustonen, Sebastian Hilli, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Veli-Matti Puumala and Aulis Sallinen. In the 2018-2019 season, works by Fagerlund, Wennäkoski, Auvinen, Jukka Tiensuu, Kimmo Hakola, and Ville Raasakka were performed by the FRSO and works by Joonas Kokkonen, Sallinen, Rautavaara, Jaakko Kuusisto and Wennäkoski were performed by HKO. There is little overlap between the two orchestras (except both performed works by Sallinen), and both orchestras featured works by a wide stylistic range of composers, and composers who are ages 28 to 83. Also note the sheer number of composers, nineteen, performed by only these two orchestras over two seasons.

Finland’s neighbor orchestra, the Swedish Radio Symphony, also played a proportionally large amount of Finnish music over the past two seasons. In the 2017-2018 season, 48% of contemporary music performed by the Swedish Radio was by Swedish composers, but 29% was by Finnish composers Sauli Zinovjev, Rautavaara, Sallinen and Kaija Saariaho. In the 2018-2019 season, it was even closer, where 26.6% of contemporary music performed by the SRSO by Swedish composers and 20% by Finnish composers Salonen, Rautavaara and Wennäkoski. In the past two seasons, the Oslo Philharmonic, Royal Swedish Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra and Los Angeles Philharmonic also performed Finnish contemporary music by composers Salonen (OPO, NYP and LAP), Saariaho (OPO, RSPO, BSO, LAP) and Lindberg (Philadelphia). In the 2017-2018 season, the NYP featured also compositions by Danish composer Bent Sørensen and Icelandic composers Daníel Bjarnason and Anna Thorvaldsdottir but in the 2018-2019, Salonen and Saariaho were the only Scandinavian/Nordic composers performed.

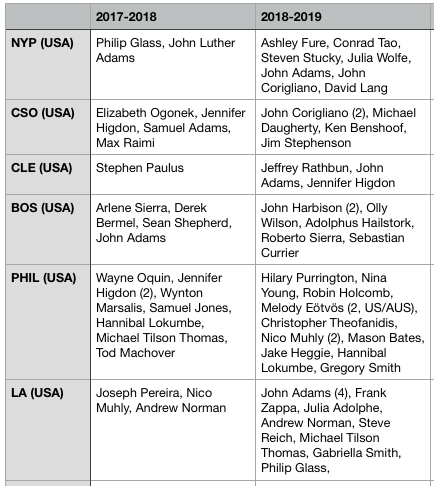

In the United States, there was a large increase in contemporary American composers performed in the 2018-2019 season compared to the 2017-2018 season. In the 2017-2018, twenty different composers were performed by the six American orchestras surveyed. Only works by Jennifer Higdon were performed by the CSO and Philadelphia Orchestra, otherwise each orchestra performed completely different composers. In the 2018-2019 season, thirty-five different composers were performed across the United States by these six orchestras. In this season, works by John Adams were performed in New York, Cleveland, and Los Angeles and works by John Corigliano were performed in New York and Chicago. John Corigliano and Philip Glass, at 80 and 81 respectively, are the oldest living composers performed, while composer/pianist Conrad Tao is the youngest, at age 24.

Internationally, there was also in increase this season in American composers performed. Shown at right, we can see that composer/conductor John Adams has been regularly performed by the Finnish Radio Symphony, as well as by the RSPO (‘17-’18) and OPO (‘18-’19). Where only four American composers were performed by these Northern European orchestras in 2017-2018, eight different composers were featured in five out of six orchestras in 2018-2019, with Adams being performed in Finland, Sweden and Norway and Higdon performed in Finland and Sweden.

*2017-2018 season at left, 2018-2019 season at right.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Two seasons into this study, we can observe parallel patterns between how much contemporary is getting played, and which composers. In general, there exists a trend amongst orchestras that perform the least amount of contemporary music to perform more premieres, whether they be world premieres, national premieres, or regional premieres. I refer to this as a ‘traditional practice’, of focusing contemporary music performance only on very new music, and using the prestige of a premiere to attract audiences. Amongst orchestras that perform more contemporary music, most of the orchestras in Northern Europe for instance, there is less of a focus on premieres. There exists a more established practice of including contemporary music regularly, such that premieres need not be a special focus for artistic or marketing reasons.

In terms of commissions, there is a strong tendency in the Northern European orchestras to commission national composers. In some cases, other European composers are commissioned, but for the most part, there exists a strong practice of only commissioning composers from the orchestra’s home country. This trend does not carry to the United States, where some orchestras will commission only American composers, but on average, less than half of all commissions from the six American orchestras studied are for works by American composers.

Finally, in only two seasons, we can make a number of observations regarding the performance of Finnish and American composers nationally, and internationally. Finnish composers Kaija Saariaho and Esa-Pekka Salonen appear to be the most widely and regularly performed Finnish composers. John Adams is, in initial study, the most widely performed American composer. It is notable that both Adams and Salonen are conductors, who are known for conducting contemporary music and their own compositions. Salonen especially has had a long and distinguished conducting career in the United States. The 2018-2019 season saw a growing number of American composers being performed in Northern Europe, as well as in the United States. Only subsequent reports in the coming seasons will be able to confirm any trends.

Appendices

The following tables show the compiling of data that was used for this report. These tables were created by me, from the data collected in part 1 of this season’s report.

Appendix 1

2017-2018 season orchestra data, showing amount of Premieres and Commissions within the season. Columns marked “Finnish”, “American” and “from own country” show the number of contemporary works that were Finnish, American, or from the orchestra’s home country.

Appendix 2

2018-2019 Season orchestra data, showing amount of Premieres and Commissions within the season. Columns marked “Finnish”, “American” and “from own country” show the number of contemporary works that were Finnish, American, or from the orchestra’s home country.